Synthetic Biology Technology has brought us to the point today that the UK has accepted one of the COVID-19 vaccines for distribution, with the promise that distribution will begin soon. This result has taken just 10 months, how have the pharmaceutical researchers managed to do this? Through advances in technology.

In reality, there are different types of COVID-19 vaccine currently in trials:

1: Live attenuated vaccines

Some well-known vaccines for other infectious diseases are based on weakened versions of a virus. These are known as live attenuated vaccines.

The viruses are weakened to reduce virulence by culturing cells in a laboratory, and then processed into a vaccine. After people come into contact with these attenuated viruses through vaccination, the virus will not be able to replicate easily in humans. As a result, our immune system has enough time to learn how to fight against this weaker form of the virus. This approach enables us to become immune without getting sick.

2: Inactivated vaccines

Inactivated vaccines contain viruses or bacteria that have been killed, which are either whole or in pieces. When our immune system detects these dead viruses or bacteria or their fragments, it can learn to recognise the fragments. After this, we are protected. If we are infected by the live version of the virus or bacteria in the future, our immune system will recognise the virus or bacteria and respond more quickly to protect us from infection – so we will not become ill.

3: Subunit vaccines

If the vaccine only contains particular pieces of a virus or bacteria, it is known as a subunit vaccine. When that subunit can be recognised by the immune system, it is referred to as an antigen.

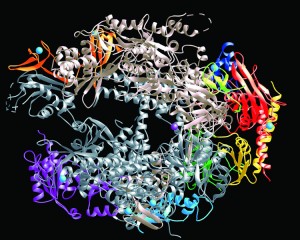

Extensive research is being carried out on subunit vaccines for protection against COVID-19. An important subunit of SARS-CoV-2 is the spike protein or S protein, which is attached to the exterior of the virus. The virus uses the S protein to make contact with another protein which is located on the exterior of the cells in our lung vesicles. If the virus attaches itself to a human cell via the S protein, the virus can penetrate the exterior and enter the cell. Then the cell is infected. Because the S protein plays such an essential role in the infection process, it is targeted by many vaccine developers. If we are infected by the live version of the virus in the future, our immune system will immediately recognise the virus and we will not become ill.

4: mDNA and mRNA vaccines (m stands for messenger)

DNA and RNA vaccines add a new piece of genetic material – deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) or ribonucleic acid (RNA) – to specific immune cells in our body. The targeted cells are often a particular type, which absorb and break down a virus or bacteria. The immune cells that have broken down a virus or bacteria then show a piece of the virus or bacteria (a subunit known as an antigen) to other immune cells so they learn to recognize the antigen. That is why these immune cells are also referred to as antigen-presenting cells. The cells that learn to recognize the antigen are called lymphocytes. DNA and RNA vaccines allow the antigen-presenting cells to detect a piece of the pathogen without the cell first having to absorb and break down the live version of the virus or bacteria. If we are then infected by the live version of the virus or bacteria in the future, the lymphocytes will recognize the antigen for the pathogen, neutralize the virus or bacteria, and we will not become ill.

There are also DNA and RNA vaccines that use ‘normal’ body cells instead of immune cells. These cells also present the antigen to our immune system, which ensures that we will not become ill if we do get infected.

These DNA and RNA techniques are new, and a DNA or RNA vaccine has not yet been approved for any human disease. A number of DNA vaccines have already been used successfully for animals.

5: Vector vaccines

Researchers can modify existing viruses to act as vaccines. Once that happens, they are no longer viruses, but vectors. The viruses have been adapted in such a way that they do not display exactly the same behaviour as unmodified viruses. The difference compared to the real viruses is that vector viruses:

- can no longer make someone ill;

- (often) cannot replicate themselves, and;

- not only contain their own RNA or DNA, but also have a piece of RNA or DNA from another virus within them. All pieces of RNA or DNA can work as an antigen, so the cells in our immune system will react to the vector virus as well as to part of the vaccine virus. This is how immunity is developed.

A category of viruses that are often adapted into a vector are the adenoviruses. Adenoviruses are a group of viruses to which people are often exposed, but which cause no or only mild illness. Because adenoviruses are so common, our immune system is very good at dealing with an adenovirus infection.

This article in Nature goes into further detail.

The vaccine approved today in the UK from Pfizer/BioNTech is an mRNA vaccine. This is cutting-edge technology, and the first time such a vaccine has been approved!

To produce an mRNA vaccine, scientists produce a synthetic version of the mRNA that a virus uses to build its infectious proteins. This mRNA is delivered into the human body, whose cells read it as instructions to build that viral protein, and therefore create some of the virus’s molecules themselves. These proteins are solitary, so they do not assemble to form a virus. The immune system then detects these viral proteins and starts to produce a defensive response to them.

Synthetic Biology!